Let’s start with Duilian, the installation you will present in Geneva, a work that deeply impressed us with its intensity. It is complex, organic, and at the same time touching and personal, with a structure that wraps itself around a cinematic core that feeds energy and dynamism to all of the elements in the installation: sculptures, pictures, the environment itself. How was your project and the decision to concentrate on a feminist martyr of the Chinese Revolution, Qiu Jin, conceived, and how did you compose and articulate your work in its various aspects?

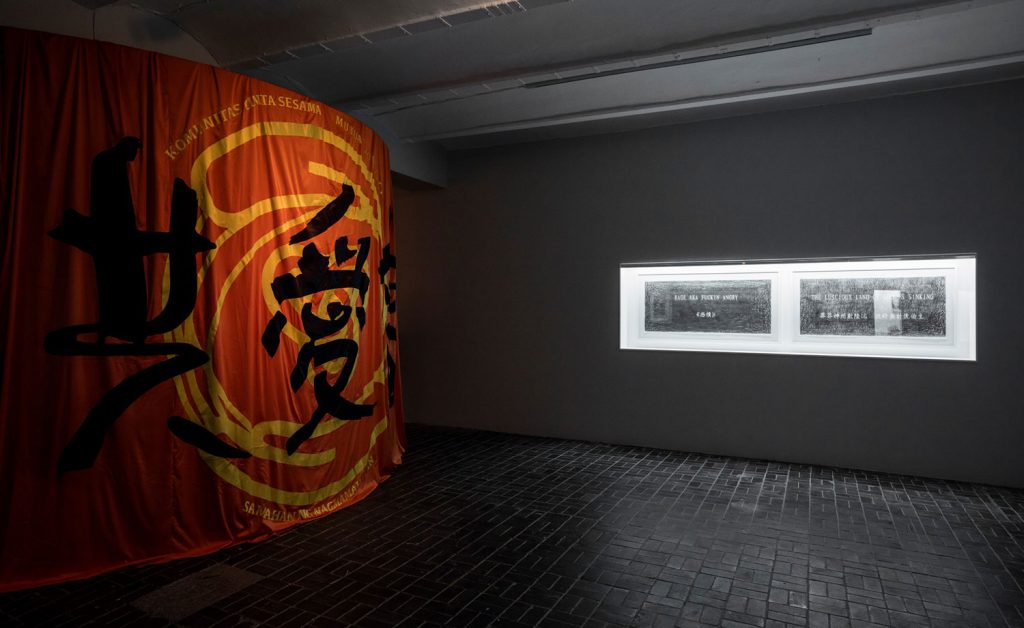

This project began more than ten years ago, with a personal story. My father and his family fled China during the Communist Revolution, and I was raised in the States without much understanding of his language or history. I always desired to “discover my roots,” so to speak, and when I went to China for the first time in my early twenties, it was very different than I imagined. I had a sort of identity crisis when I realized that I did not belong or fit in. But on that same trip I was drawn to research Qiu Jin, because I heard a rumor that she was a lesbian. In her small town, there is a museum where I discovered her relationship to Wu. Their story turned out to be even more complicated and beautiful, beyond the bounds of any cultural or sexual identity. So in the end, my fantasy of finding an “origin story” was crushed, but I was able to create a queer mythology that feels somehow more true. The project exists in several forms: mainly a film, which is presented at the Biennale of Moving Images, and also a performance with boychild, and an expanding archive that is composed of both “real” and constructed artifacts from the story.

PB/GB: The reframing process seems to play an important role, both narrative and geographic: the Chinese Qing Dynasty and modern Hong Kong. There is, however, a pure sentiment, a light intimacy, in the narrative, a complicity between you and boychild that destabilizes the separation. As spectators we absorb Duilian with a universality that transcends the historical issues.

WT: I did not originally plan to film in Hong Kong, but once I started working there, I discovered that it was a meaningful context because it enabled me to dispense with conventional notions of identity. Hong Kong’s diverse queer communities and its troubled relationship with mainland China became the backdrop for the film. I wanted to express through that the idea of history as never extricable from the present, and that queer histories are excavated through our desires to “read between the lines” of the past.

PB/GB: In your earlier films and performances, you used the voice as a metaphor in order to represent “who is speaking for whom” and “whose voices are heard, and whose are silenced.” Here you seem to find a vehicle also in the bodies.

WT: Actually Duilian is very much about voices as well. The script is composed of many different layers of research, and ultimately took form through a series of “mistranslations” that I orchestrated with many friends. The idea was, okay, if history is a lie, then let’s rewrite it and say what we want to say. So we used Qiu Jin and Wu and Xu’s poetry as the basis for something else, something that grew out of our relationships and imagined queer community. There are five languages in the film: Cantonese, Mandarin, English, Tagalog, and Bahasa Indonesian. Each of the voice-overs is performed by someone who came up with their own translation. The bodies also become a vehicle in the sense that the martial artists invented their own choreography in response to the poems I gave them—so the movement becomes a kind of poetry, too.

PB/GB: Performance is often a starting point for your films. You will present also You Sad Legend, a project that is part of an ongoing collaboration with boychild. What’s the connection with Duilian?

WT: Duilian and You Sad Legend are very much intertwined, in terms of the content and also the process of creation. My collaboration with boychild is central to both projects, but we play very different roles in each. With You Sad Legend (which is the latest iteration of Moved by the Motion), boychild and I work together as collaborators without defining the roles so clearly. Sometimes we divide tasks, like she may propose the lighting, while I might propose a narrative structure, but ultimately we share in the decision-making process. Whereas with the film Duilian, my role is more as a director and boychild as an actor. Duilian is based on a decade of my research, but I also believe that it would not have taken its shape without boychild, because our creative dialogue extends into so many things. We often travel together and share in life, and our art extends from this life, as well as the lives of many others. It actually makes me think of a poem that Qiu Jin wrote for Wu: “Mutual affection drove us to explore the world together / for good companions, encounter means happiness.” I guess I chose the lines of poetry that felt most resonant with my own life, and created the possibilities for the most ambiguous readings.

PB/GB: The sound is extremely important, beginning with the theme, which explodes your pain and melancholy, to the voice-over alternating with your whispered dialogues. How did you work on the soundtrack?

WT: Before this film, I never felt the need to work with 5.1 surround sound, but in this case the multiple channels became essential because I could layer many voices without the sound becoming too muddy. Although we shot to a script, I really discovered the narrative through the editing process, with the voice-over being a guide. It enabled me to create varying fields of lightness and density, so that the slippage of persona and time period could be fluid. The musical score was created by Asma Maroof (DJ Asmara) in collaboration with boychild.

PB/GB: It is interesting that you chose to use Chinese characters in lateral subtitles to mark the more textual parts; this serves as the narrative glue of the whole story. Are those Qiu Jin’s poems that we read? How did you use her texts, and how were they translated?

WT: The Chinese characters are actual duilian (couplets) that were written by either Qiu Jin, Wu Zhiying, of Xu Xihua. Viewers might have a different experience depending on what languages they are familiar with, because there is an intentional discrepancy between the original source material and the mistranslations, which were created through a process of engagement with queer communities in Hong Kong. I wanted these discrepancies to highlight the fact that language is by nature inadequate, especially in the context of expressing desire. So the film literally exists “between the lines” of official traditional Chinese poetry.

PB/GB: Qiu Jin is a larger-than-life figure, a sort of modern Joan of Arc: mythologized as a warrior, and also as a poet, editor, orator, feminist, and revolutionary whose exploits are today immortalized through films, television series, theater plays, and even museums and monuments. We are curious to know how you worked with Qiu Jin’s existing iconography, and if and how this project incorporates all of these preexisting discourses and elements.

WT: After years of researching Qiu Jin, I felt familiar enough with her dominant narrative to want to challenge it, to see what alternative forms of representation might be possible while still respecting her history. I particularly questioned people’s tendency to eulogize her as a martyr and their obsession with her brutal death and self-sacrifice. I mean, those things are true, but I also think it’s more complicated than that. She was a real person with faults and a personality. By reading through her intense relationships with other strong women in her life, such as Wu Zhiying and Xu Xihua, I began to imagine a different sort of character, who took on even more life as I started working with boychild, to translate Qiu Jin into a modern context. We had a running joke that she was a “messy revolutionary” or a drama queen, and according to some scholarly interpretations, I really think you can see her that way! It made the performance more playful, and more human.