Let’s start with the thinking around Mutumia, your work made for the Biennale of Moving Images. How did the project come to be?

I was sent a picture by the Ugandan poet, essayist, novelist, academic, and dear friend Juliane Okot p’Bitek. It was an image of a group of elderly Ugandan women naked and prostrate on a dusty path. When I saw it, my immediate thought was, “Oh god, what is happening to these women, what is being done to them?” We are so used to the implications, the connotations, the politics of a naked woman’s body and its associations with victimization and exploitation that my assumptions and horror were kneejerk. Later, I came to learn that these were in fact Acholi women protesting for their land in front of the police, government officials, and surveyors who had come to forcibly remove them. In many African cultures, it is a taboo for a man to see his mother naked—a taboo and a curse—and this defiant act by these defiant women rendered itself a worthy weapon. Those women effected change that day. The images were heroic. I was rocked by how wrong my reading of them had been. I started researching other moments in history where women have used their bodies in protest. Professor Wambui Mwangi’s essay “Silence Is a Woman” (2013) was pivotal in this regard.

NK: That’s a powerful essay. I’m always returning to it.

PB: Me too. I have to thank that essay for the title of this work, actually. In it, Mwangi interrogates the question of bodies that are allowed to impose themselves in public and those that are not. She speaks of mutumia, the general term for a woman in Gikuyu, and proposes that it actually translates more directly to the “one whose lips are sealed.” My mother is Kikuyu, and when I asked her if this was indeed true, at first she said no, but later agreed to the logic of the translation. Which speaks of generational attitudes, doesn’t it? On a personal level, it was also frustrating to not fully understand my mother’s confusion regarding the etymology, because I do not speak my mother tongue. Language—or my lack of it—plays a big part in my work, as does my understanding—or lack of it—of my place in the world.

NK: I have been paying particular attention to your conversations on language. It is something I am curious about also because in my work I am often looking for that language that can imagine me as a Kenyan woman who is speaking or writing in English, a language that was not invented by or for me. I love what you say in “On Love, Language and Lizards” (2015) about finding your language that communicates what it means to be in the world right now and is “pliable enough to squeeze into the Kikuyu corners and also eek itself into English edges.”

PB: Yes. That’s when we met, wasn’t it? When I read that paper at Africa Writes. You tweeted that quote, I think, and I was so delighted, and then we went to the pub and drank red wine and ate North London out of nyama, and set the world to rights. But yes, it has taken me a while to find my “language,” a language that can contain all my contradictions. This is not to say that the process is complete. But in the realization that I need this language, all the work I make now nestles somehow within that exploration of building up this layered, robust language. I draw, I animate, I use projection, sound, I write, I make films sometimes, I am beginning to test the waters of interactivity, I make installations that mash up all these things, offering them to the audience to enter as they choose. There’s a freedom in this.

NK: It’s really about finding that middle ground, that middle language, that can accommodate all these things.

PB: Indeed, that can accommodate, and even celebrate, the nuance. So anyway, in honor of language, calling the project Mutumia was important. And somehow, in the simplicity and the complexity of that title—“woman” versus “the one whose lips are sealed”—the formulation of what Mutumia was going to be unwrapped itself quite spontaneously to me after that.

NK: Why was it important for you to do this project?

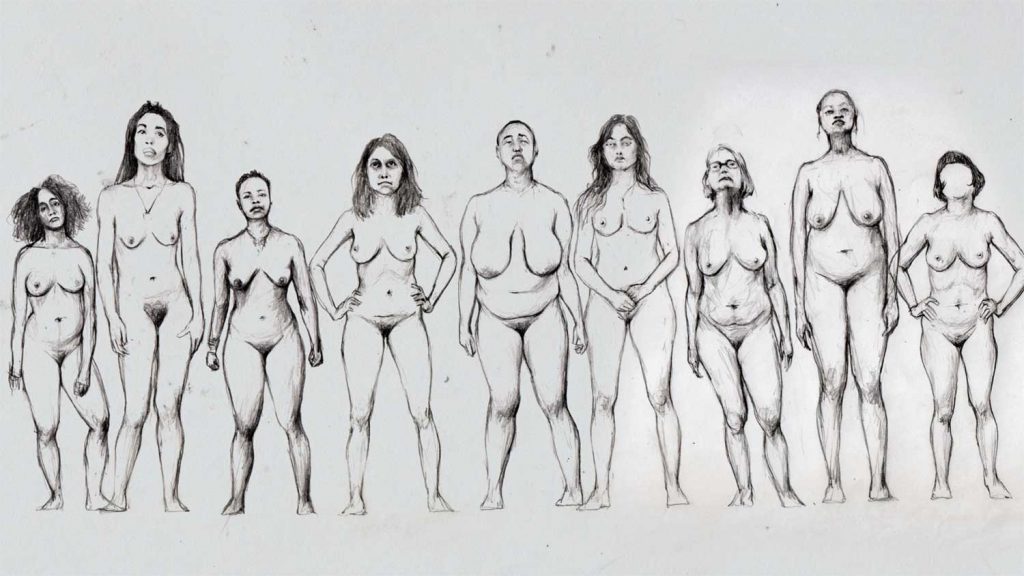

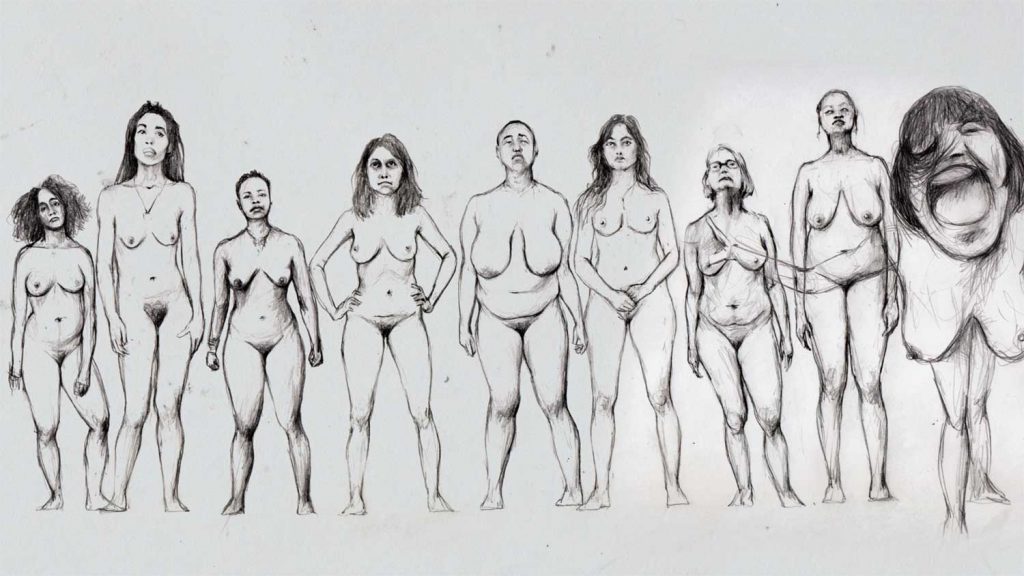

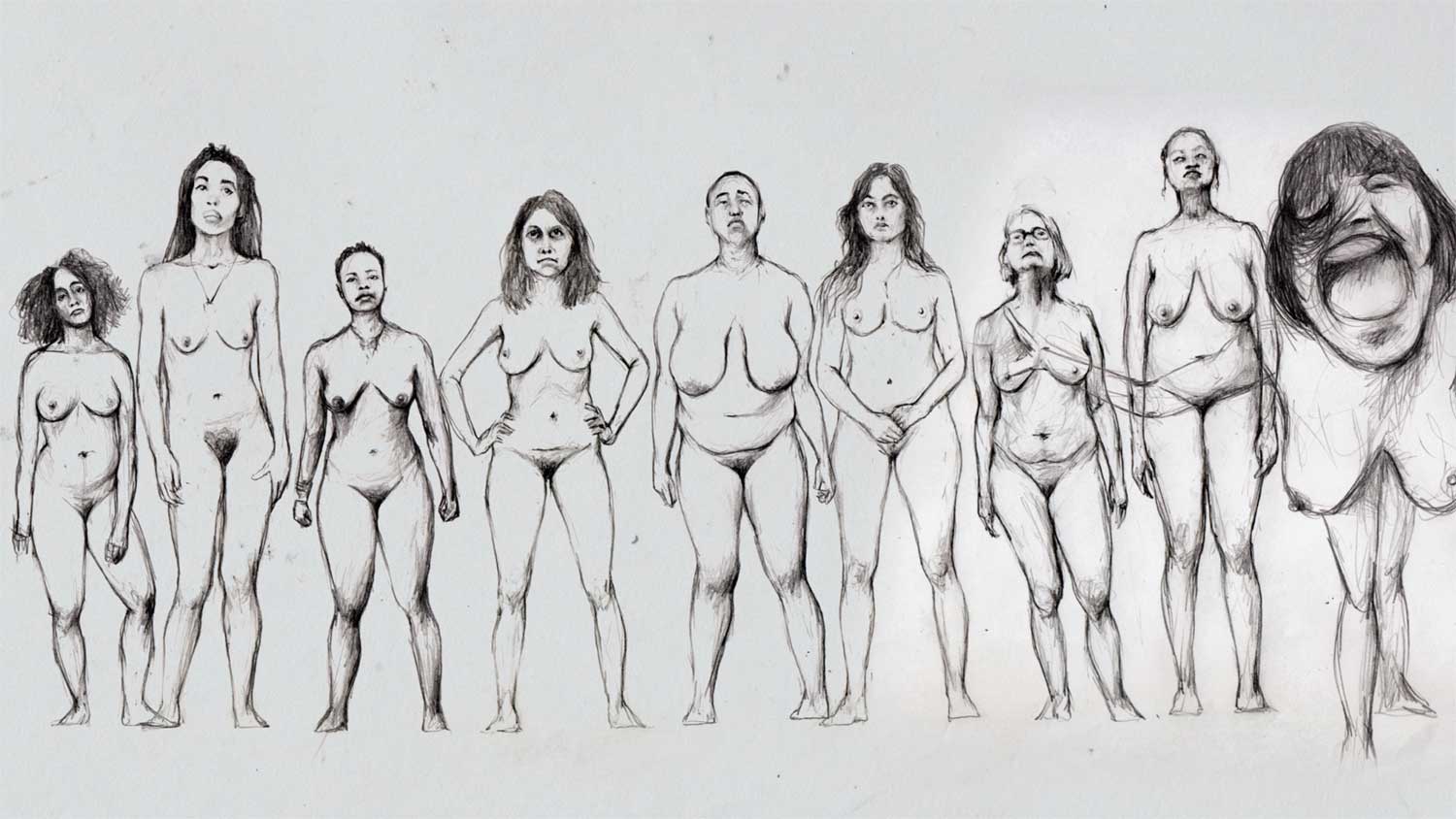

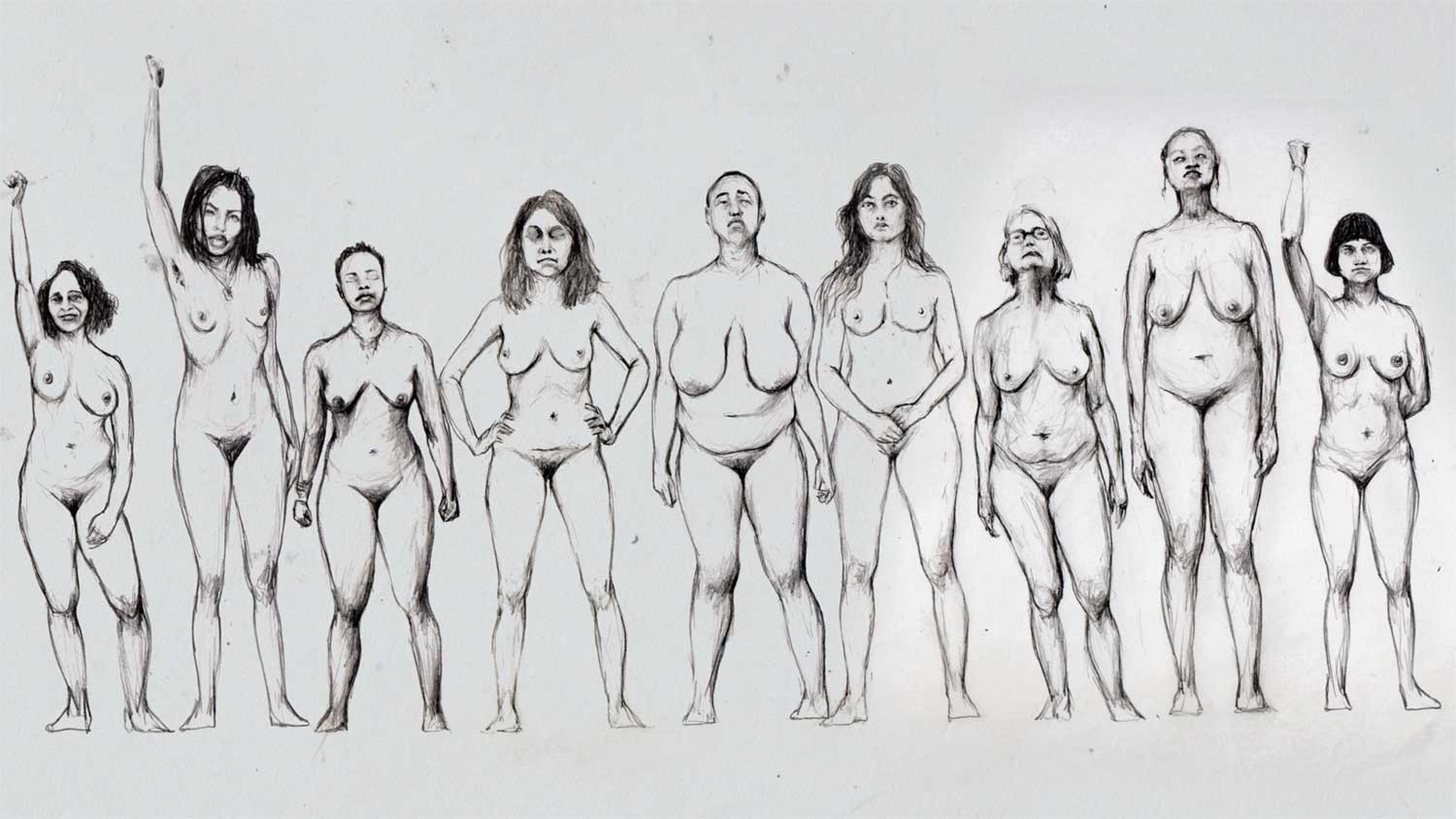

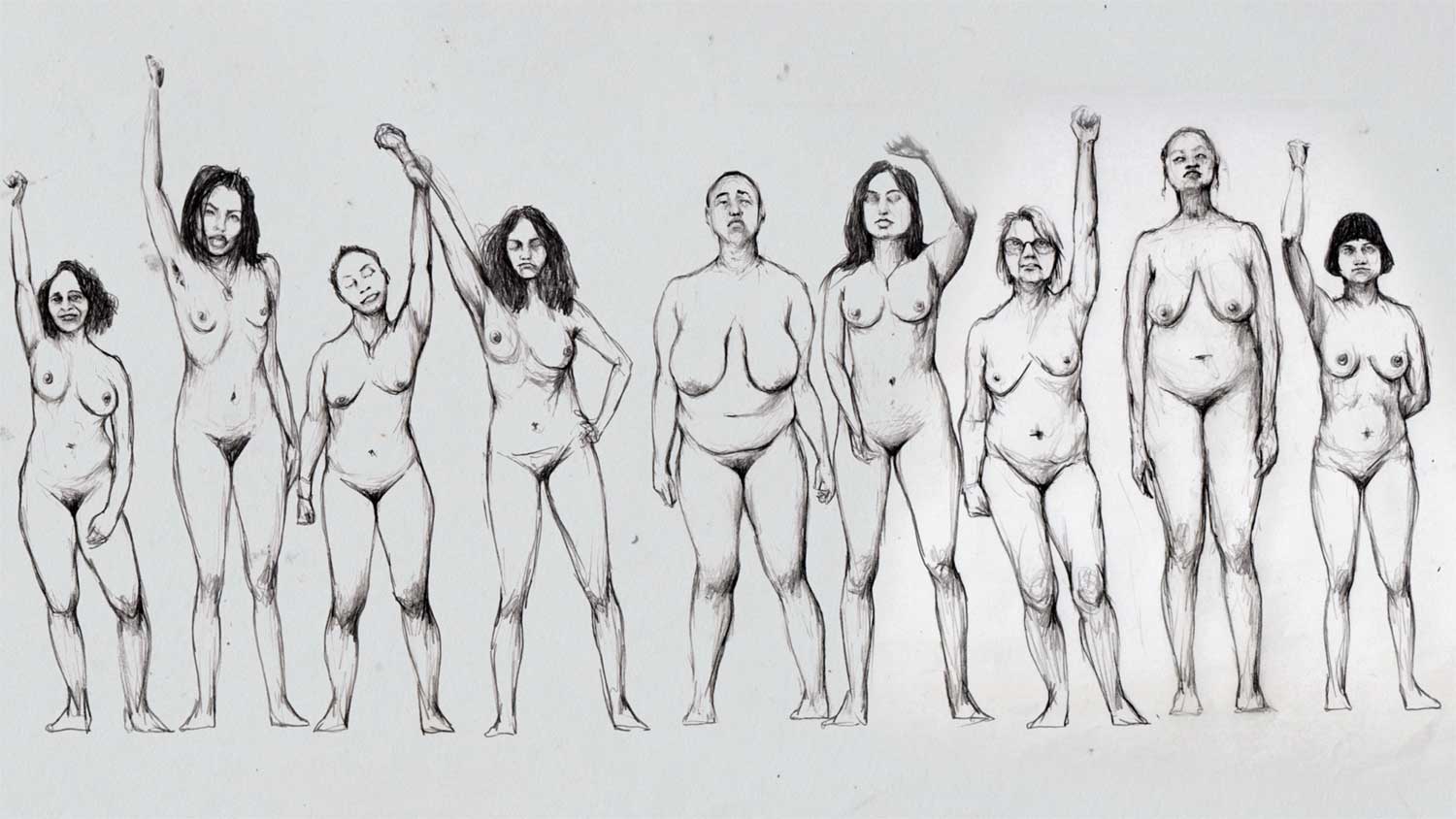

PB: I wanted to salute these women who have altered history but perhaps have not been heralded or written about for doing so—because, as we know, history books are usually written by men who often leave out the narratives of women. I decided to create this “army” of naked women who would confront the viewer as they enter the space. This was also to confront the lack of visibility of women in the white-male-dominated spaces of the art world. The Guerilla Girls just released a survey showing that only two art museums in Europe show more than 40 percent female artists. I mean, what the actual eff? I wanted to permeate the walls with these hand-drawn women, and force you, the audience, to confront them in the space.

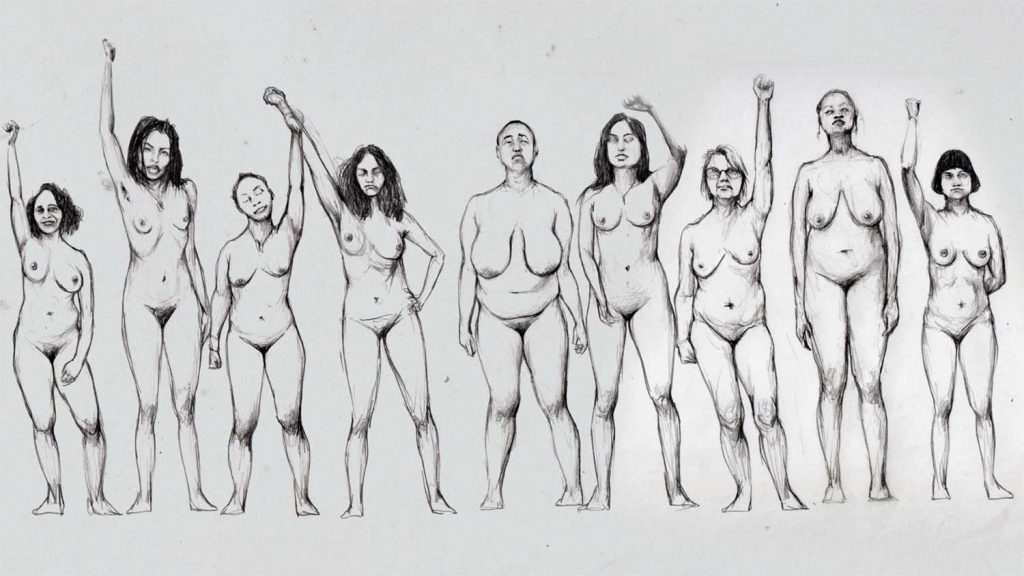

The piece is interactive. The room is fitted with sensors that sense your presence; your acknowledgement of the women in the space activates female voices. I want this sense that we are all standing together in this army, propping one another up, enabling one another to be heard. This was a commission for the Biennale of Moving Images, which strives to push the boundaries of what the moving image can be. I also wanted to push my own practice and the audience’s sensory experience of my work in terms of interactivity and creating a drawn, animated world. I was lucky to work with Andrea Encinas, Leonn Meade, and their incredible B.I.G. Choir on the vocal elements of the piece, and with fellow artist and brilliant coder Fabio Lattanzi Antinori on the interactive sound element, which has been so exciting for me.

NK: I am curious about the process of developing these ideas around mutumia into a concrete project.

PB: The process became part of the work. I wanted the women I drew to be nuanced, real bodies, so I put a call out on social media, asking women to take part in the visual reference gathering. I was amazed when so many women I admire—curators, writers, artists, musicians—acknowledged my call to arms. They brought so much of their own stories, their traumas, the stories they tell through their bodies to Mutumia. In my studio, one on one, we would do these filming sessions where I would ask them to consider various emotional aspects of protest, and I filmed what happened to their bodies. I didn’t ask them to perform, but to sense themselves. We explored anger, despair, shame, joy, freedom, strength. It is so special for me that you and I are having this conversation about Mutumia since there’s a part of the piece that was inspired by your essay “The Khanga Is Present” (2016).

NK: I was very honored when you first told me that that essay had inspired you. When writing it I was thinking of my mother, my grandmothers, all women who have been there before me and how they found and continue to find unconventional ways to speak of their pains, their desires, their bodies, their anxieties, and yet how this protest is absent in the collective memories of Kenya.

PB: Yes, and truly, thank you for writing it. I asked these women to imagine the place in their bodies where communication between women and womanhood existed. They chose their womb, their heart, their head, and so on. From these places they drew out an imaginary khanga, which I animated. So in this moment, they all become khangas, and for a moment it stops being a group of women confronting you but a wall of khangas. It’s a comforting moment, I hope. Being immersed in them. So I thank you for that! It’s fleeting, though, that moment.

As the installation proceeds, implicit bloodstains appear on the khangas, exploring another aspect of what it means to be a woman. Each woman taught me something about the work. They all came for their own reasons, to challenge themselves, to challenge the patriarchy, to realign with their bodies post-surgery or post-childbirth, to empower themselves by claiming their bodies back from ideas drilled into them by parents or partners or lovers or strangers on the street. It was an extraordinary privilege of a process. I set up a Facebook group to coordinate these sessions, and it became a place to share articles, art, et cetera, that supported the themes of the work.

I then animated for months and finally began to work on the sound. I wanted to explore the female voice, to see what it is capable of. So all the sound in the piece comes from the mouth. Clapping, birds whistling, wings flapping, trees creaking, and so on. I worked with a gospel choir, and as a group we explored the same themes I had gone into with the women individually in my studio. Together, the women laughed, cried, sang, punched the air out of themselves, grieved. Again, such an immeasurable experience. I’m now at the point where I’m putting it all together, and it feels like I won’t truly know what the piece is or does until the first person stands within it in Geneva. There’s a phenomenology to interactive work that one can’t account for in the privacy of the studio. I’m excited, though. And fucking terrified.

NK: You have mentioned Professor Wambui Mwangi as someone whose work has helped you think through this project. There is usually that sense that we are always in conversation with other people who have been there before us or others that we continue to think with. In your recent installation Stranger in the Village (2015), you borrow from James Baldwin to explore the perceptions of black women in predominantly white space. What other artists, thinkers, or theories would you say you have been in conversation with for this project?

PB: Whenever I read your work, I always get this overwhelming sense that we are in conversation. Perhaps because in your writing, like with my work, you are trying to find multiple inroads for your audience and trying to expand the space for imaginations. Baldwin is a huge hero of mine—the bravery and generosity through which he evoked the personal to speak for the public. In that project where I referenced his 1953 “Stranger in the Village” essay, I was sort of challenging him on it a little. I was on a residency in Sweden and had been told that Gothenburg society was very segregated, so I immediately thought of his essay, which I’d previously had a hard time grappling with, since my experiences with race thus far had not been extreme. Using his title as my tag, I decided that the most efficient way of exploring my brown body in this space that might not be so welcoming of it was to set up a profile on Tinder and start swiping right. The piece was a collection of intimate drawings of all my Tinder swipes and their opening gambits, which, much to my dismay, contained all the types of othering Baldwin describes in his essay. I understood him better after that project.

In terms of theories and (recent) history’s voices, I’m obsessed with Umberto Eco’s theory of the open work. For a long time, and it’s the main reason for the multiple inroads I require in my work, I believed that my voice was sort of neither here nor there, invalid, nonspecific, owing to my heritage and transient upbringing and so on, which I have spoken about a lot. Édouard Glissant has buoyed me in this regard, with his notion of the poetics of relation: how we can celebrate all the minute differences that make up the world, in tandem not opposition. His writing exists in the middle space, the ocean between here and there, and I gain a lot from taking ownership of the fact that I exist there, too.

When I was making The Matter of Memory (2014), for instance, it was the first time I had made work about “home,” and honestly it felt very fraudulent to assume I had the right to do so. Because something was telling me, “You are not reeeeeeally Kenyan, you don’t belong there.” In the end, The Matter of Memory became the only thing it was ever able to be, which was an honest exploration of the intimacy of the contradictions in my own home, my family home, and (because the personal has a way of rendering itself universal—the micro becomes the macro—the personal is political) it opened up the possibility of exploring the contradictions of Kenya’s colonial past in an open way. It opened up the brutality for reexamination.

Actually, again, I owe that title to someone else; the very brilliant Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor, whose novel Dust (2013) gave me life at one of the many self-conscious moments in the making of the work. What I realize is that this middle space can function toward creating work that doesn’t fix the response to it—open work. This approach has the ability to fix previous histories, to rework them, to invite or encourage the viewer to see things differently without forcing them to see things one way. Which has allowed me now to believe that my voice actually does have some validity, a purpose.

I always think of Chimamanda Adichie’s cautionary: beware of the single story, too. Meanwhile, as the world is going through this time of deep reflection and heightened social consciousness, we all have the responsibility to see ourselves truly within the systems that limit us and others. I am in the process of reexamining and negotiating the inherent privilege of this middle space. In many ways I grew up appreciating the freedom of not feeling bound to a nation-state, a race, a religion, all of these categorizable signifiers the world insists upon. It’s important, though, not to blindly defend that position in order to exist outside the difficult conversations. We are all responsible for dismantling the systems that bind us all. And these conversations are being had now, which is good.

NK: So you feel a responsibility to make identity-based work?

PB: I mean, the world is shit right now. Brexit, Trump, pervasive rape culture, the fact that we need to state that Black Lives Matter, the fact that brown bodies are continuing to drown in muddy political waters. I think that right now, more than ever, artists need to be making work about what it means to be human. It’s impossible not to be political. Even if an artist chooses to make nonpolitical, non-identity-based work, that choice in itself is political. In London, hipsters are being hailed as the new face of capitalism; artists the henchmen. What has happened? Making art right now is about adamantly rejecting the shit of the world, addressing it in order to subvert it, claiming space, making the stuff we want to see more of, and utapoa, we will all be better, one of the few things I actually know in Swahili. That’s what it means, right?!

NK: Yes, you’re right. I have to mention one last thing. Mutumia has made me think of what is happening in South Africa right now with the university protests: how young women are following in the footsteps of our grandmothers and baring their chests in protest. These women are confronting the world with this body that is so hated, so violated, so invisible, so easily forgotten. And it is such a powerful resistance. I am in awe.

PB: So am I. They are forcing the world to look at them and they are saying, enough is enough! We refuse to be invisible. We are tired. Aren’t you tired?

NK: I am.