For the Biennale of Moving Images, you are about to show Exquisite Corpse, a film work that you recently did about the Los Angeles River. The film was shot along the course of the river, from its point of origin in the San Fernando Valley to its terminus at the Pacific Ocean. Along the way, you encountered diverse landscapes, and animals and humans that live in and around it. As a Los Angeles resident yourself, why did you choose this specific river? Is there a particular reason, a particular moment or event, that led you to take this natural element as a subject? What was your original aim as you prepared for this “river movie”?

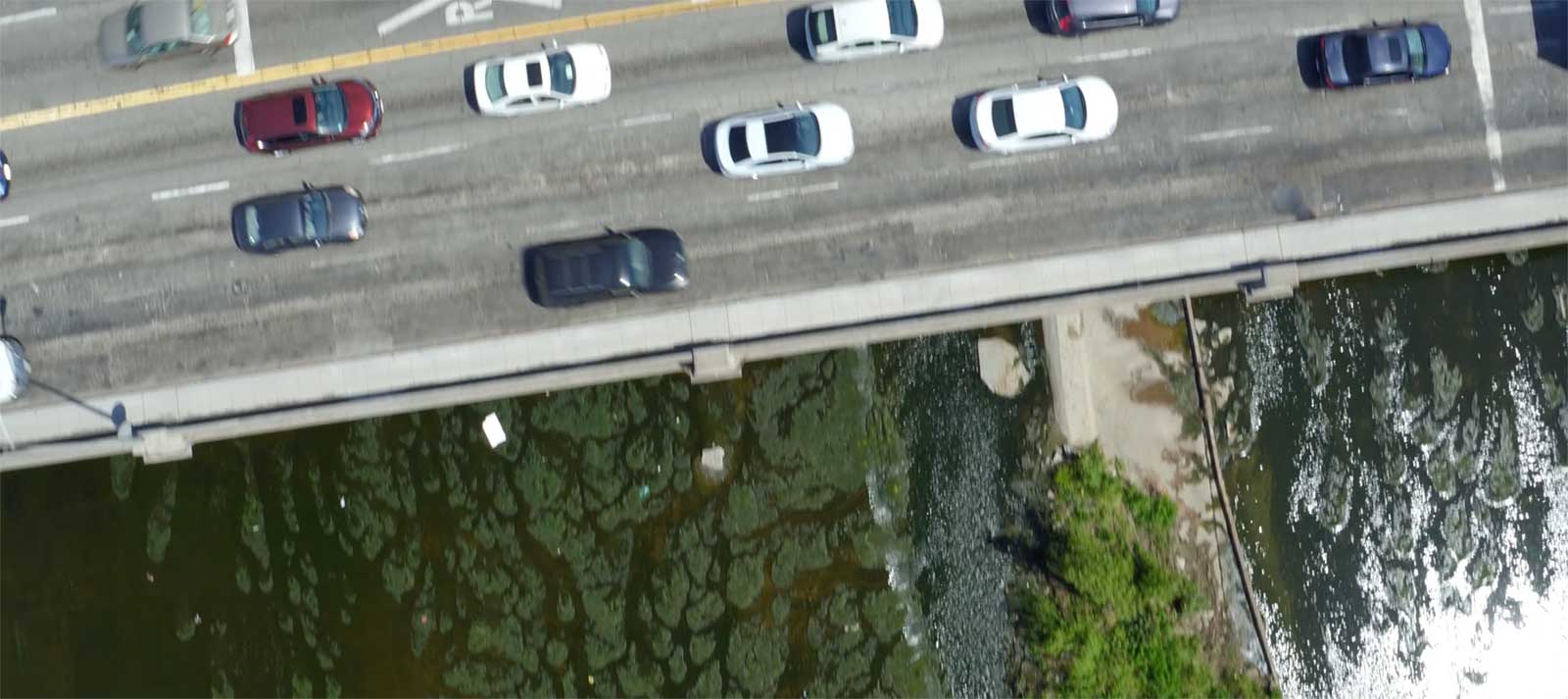

Back in 2003 I had a studio that was a block away from the river, so I drove over it regularly but never really thought to look down. My current studio is also just blocks from the river, but in the intervening years gentrification has transformed the area. Interest in the Los Angeles River has skyrocketed, and parcels along that part of the river are being fought over by developers who feel they’ve discovered the last great frontier of L.A. real estate. The river is in a constant state of flux, changing faster than anyone can document. Since filming, the landmark 6th Street Bridge downtown has been completely demolished and the rubble carted away. You can see half of it still standing in one scene of my film, and it’s fully intact in the next. When I was invited to propose an artwork for the city of Los Angeles, I decided to site the work in the public park that sits on the river halfway between my old studio and my new one, and decided to make a film that would trace the river at this particular juncture in its evolution. I entered with a sense that I would just picture whatever I found, and wanted to make something in which that spirit of discovery would carry over into the resulting film.

YC: Of course your work is not only about the river itself: it also seems to be about exploring the activity around it, natural life, communities, specific destinies. It is interesting to note that by following the course of nature, you shed light in parallel on ecological and social issues that are critical in California, as well as in many other contexts at the moment. Did you use a particular method to document the river’s ecosystem and surroundings? Did you have a specific political agenda? How did the process of traveling and filming influence your initial take on the subject

KT: The future of the Los Angeles River is a major topic of public debate at the city, state, and federal levels. Massive revitalization plans are in development, representing competing visions for the river’s future. Against this complex and highly political backdrop I wanted to make a film that would show people what is actually happening in the river, all along its length, without judgment, right now. I wanted it to be very democratic, paying equal attention to all parts of the river, not just the areas where white people spend time. I wanted to share things that most people don’t get to see and tried not privilege one kind of knowledge over another.

YC: You mentioned that you decided to edit a fifty-one-minute-long film to symbolically mirror the actual length of the Los Angeles river, which is fifty-one miles long. It is a beautiful analogy that you produced in between filmic matter and water streams, between cinema and the river’s flow. Is there any particular metaphoric meaning behind your work? In ancient Occidental texts, rivers often refer to death, the water materializing a boundary or passage between two states. On the contrary, your work seems to be turned toward life, every kind of life that develops around water.

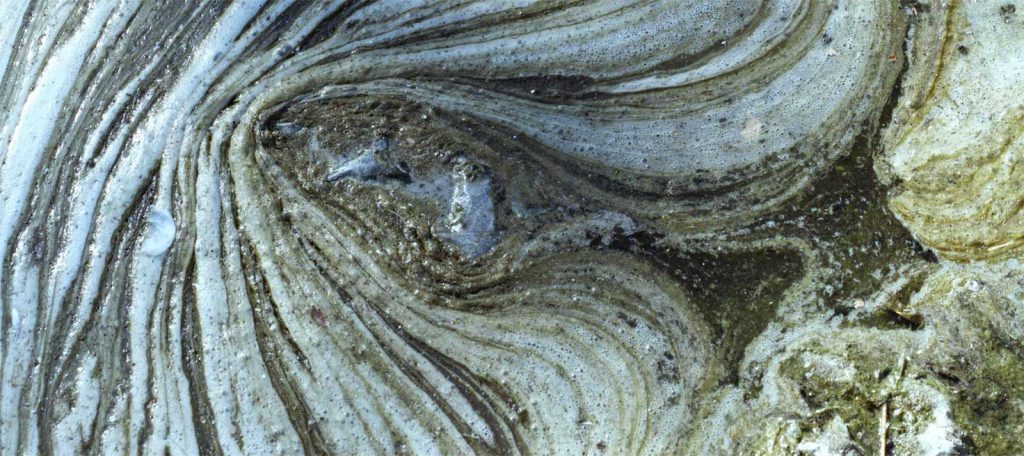

KT: I wasn’t thinking in those kinds of symbolic or archetypal terms. In fact, I wanted everything to be extremely specific. I was always reminding to my crew and my editor that in this film nothing should stand in for anything but itself. I hate inventing stories, so I was hugely relieved to find that a map could be our script, trusting that if we just spent enough time in a place, a story would be revealed. We were a very light crew, and whenever we thought we knew what to expect, the river would come up with something else. What was perhaps most inspiring was to discover the great resilience of life along the river. Even in the most barren industrial stretches you’ll see shorebirds wading in the shallows, and swallows come out to swoop you at dusk. We met an exceptionally friendly duck, leash-trained cats, and a lot of horses. Where there’s water, there’s life.

YC: The title of the work, Exquisite Corpse, is a direct reference to the Surrealists and their passion for chance, the unconscious, and random associations. Effectively the work process could evoke a form of “drift” that allows illuminations and unplanned encounters. How did this specific artistic tradition did inform your film? On another level, the film seems to distance itself from the dreamlike nature of Surrealist movies by incorporating other dimensions of cinema that deal with documentary practice, the collective unconscious of the American landscape, fiction, and more. Could you elaborate on the form of the film itself?

KT: An “exquisite corpse” is, like my film, a composite portrait created in segments, but your question beautifully articulates a more significant dialectic central to most of my work. I tend to create and then follow stringent rules (fifty-one miles in fifty-one minutes, for example) and I don’t like to make things up. On the other hand, I know that when you put images and sounds together in time (for what else is film?) all kinds of associations outside of what is strictly depicted are evoked. Every edit produces a reality that didn’t previously exist. It involves a certain leap of faith to trust that the poetry I experience in making the work will reach the viewer, but that’s usually when the magic happens.