I’ve been following your work for many years now with great delight, hilarity, and occasional tears. Something I wrote early on related to the pacing and peculiarities of children’s television, and how it had evolved in strange, complex, and interesting ways in your work. That element is still present for me but it’s been refined both technically and conceptually: the slowest movements unfurling at odd angles, the figures’ interactions with surface, the constraints of the medium, the discombobulation that can happen with time and image when pace and picture are tweaked. There’s a gaggle of questions all mixed up in there, but let’s start with: Where do your characters/figures begin? What is their inspiration, and can you describe your process of developing them?

That question has a few different answers. Many things can lead to the development of a character. Some begin as a collage, a scribble, a collection of shapes or doodles. The inspiration can vary from found bits of paper to the decorative pattern on the edge of my breakfast plate. I think I enjoy imagining a world where the most unlikely things come to life. Of course, other artists are a major inspiration, too.

AB: Personally, I breathe a lot of fantasy into these characters, wonderland charlatans, and otherworldly creatures. Do they exist in an alternate reality for you, or are they more like performances injected into reality? I guess maybe what I’m asking is: How do these creatures and situations exist in your imagination?

BB: While I’m making the costume or mask or whatever it may be, I let myself get wrapped up in the love of the process of making the object and I don’t worry too much about who he or she is yet. I guess I’m sort of waiting to get to meet it and reserving judgment until it comes into focus. That comes when I see it start to move on camera and even after, when I’m editing. The work usually takes me by the hand and tells me what it wants to be.

AB: In Man with Cigarette (2016) there’s something both kindly and menacing in the stiffness of his face and the rhythm of his movements, especially as you chop him into pieces that move in odd and independent ways. I’ve found this combination incredibly compelling—uncanny at times, even. Is this tension something you think about when you’re making your work?

BB: That tension is absolutely something I think about when I’m making the work. It’s why I spent so much time figuring out how slowly I need to move in that costume to create the subtle movement that leads to that sensation of the uncanny. But the most compelling moments often come from experimentation and keeping my radar up for the sequences that give me a chill or send a sort of wave through my body. When I get that feeling, I know I’ve caught something and I need to follow up on that moment and cultivate it (to mix fishing and farming metaphors). Perhaps I repeat or accentuate the type of performance I did to heighten that feeling.

AB: How do your ideas come together formally with the media you work with? Do concepts, methods, and materials interact and change each other in the process?

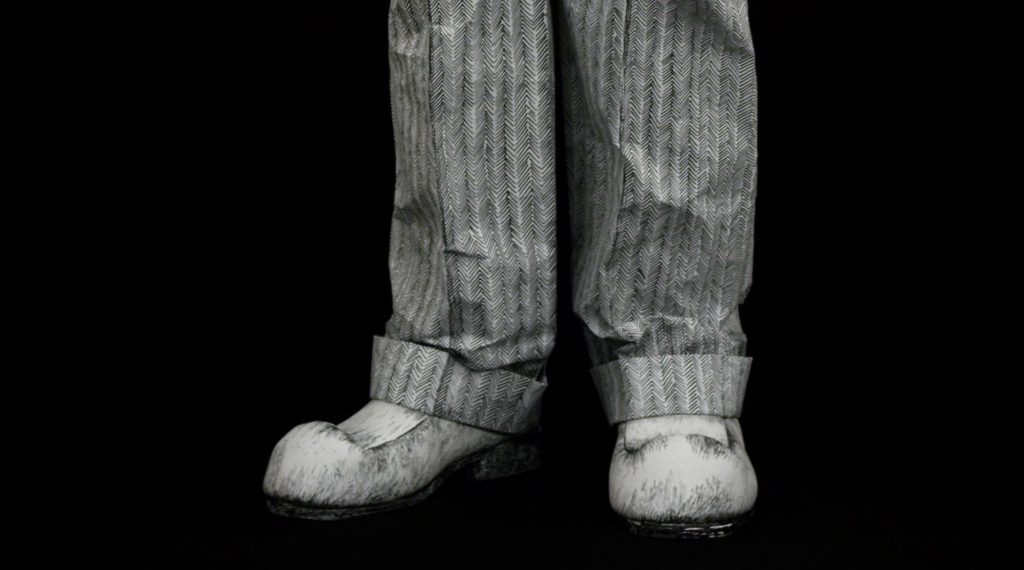

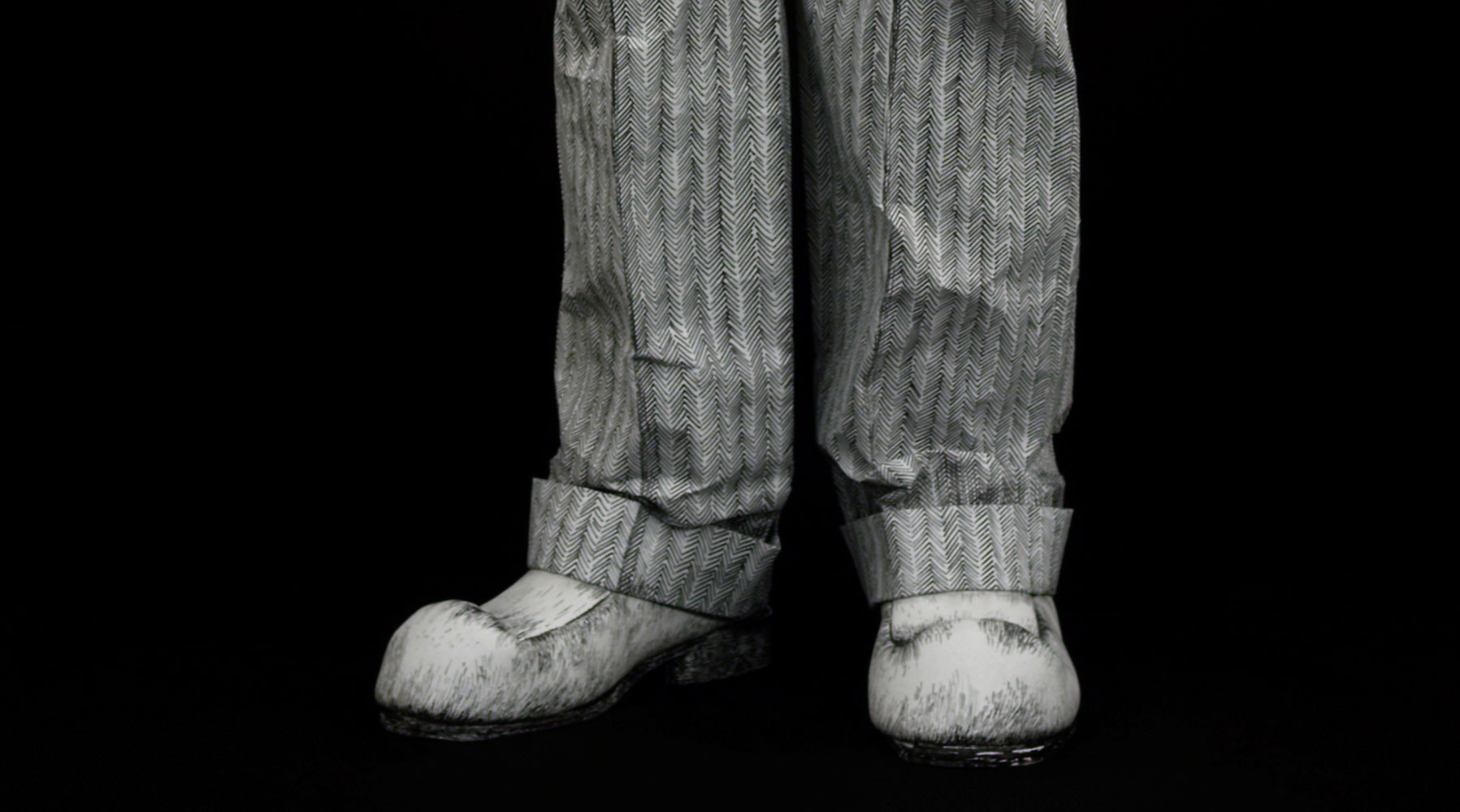

BB: That’s a great question that gets at the two-pronged inspiration for Man with Cigarette. The aesthetics of this particular piece came from a drawing I saw years ago in a thrift store. The drawing was a tour de force of pen-and-ink techniques depicting a man in a flashing checkered jacket, tie, and herringbone pants, his fedora tipped slightly forward and his hard cheeks described with loving pointillism. It reminded me of every way I tried to draw with a pen when I was a kid and up through high school. This full-figure portrait was, as I saw it, a giant love letter to drawing itself. Although the store wouldn’t sell it to me (I guess they liked it too much to part with it) I did take photos to perhaps one day re-create its awkward and beautiful and just flat-out-strange vibe. That was in 2012, and it gets at the formal drive behind the aesthetics of the piece.

Two years later, in 2014, when walking through an airport I encountered a video wall composed of four screens stacked into one tall rectangle. It was playing an advert for women’s clothing, and it showed one lady at a time walking onto the screen and posing as if on a runway. Many women came on screen, one after another. But the piece was out of sync. Some poor tech had goofed and now one woman’s head was on another woman’s torso, and still someone else’s legs were sashaying in a different dress. It was a beautiful mess and no one seemed to care but I stood there and watched this ad for clothing and was mesmerized. It seemed to me like an exquisite corpse meets a video wall. To me it was the perfect use of this awkward technology. These four screens that beg to be seen as one were finally reaching their full potential by acknowledging their limitations and using those limitations to great effect.

AB: Technology has become more present in your work over the years, most notably the wall screens but other more subtle advances, too. What sorts of challenges does this pose? Or are these technologies so common now that it feels easy or inevitable to use them as tools for making art?

BB: I both love and hate technology in my work. I love that it opens a world of new ways to create images and play with movement. I hate that I’m at the mercy of a few components and that the word “firmware” is used on a daily basis in my studio. And it’s not only the production end that can be frustrating, but the conservation side, too. I’ve been lucky enough to encounter very few problems with the work failing, but as time goes on, I know I’ll be fielding more and more technical problems from those who own the work.

Like a moth to a flame, though, I find myself drawn to these screens, to this way of showing images. We are in the age of the screen, right? Why not use it?

AB: Besides the obvious shapes of particular technologies, you’ve worked with all kinds of image and object making over the years. Can you talk about the different challenges and charms of working in different kinds of media, particularly the different kinds of moving images? How has context and time changed the different works you’ve made and what you might have learned along the way?

BB: Even since I’ve started working with moving images, folks are more than ever primed to understand a moving image as just a moving image and not needing to read narrative into it or expect that it has a beginning or an end. As far as time and context are concerned, I think that the more time that passes, the more I’m able to really understand what my work is about. Perhaps right after you make something, you’re too close to it to understand how it functions.

AB: Narrative and storytelling are interesting to talk about in your work, as much of what you’ve done exists outside of anything resembling a common narrative arc, but sometimes I’ve felt stories seep in. For example the exhibitions Under Performing—in particular the piece Creative Ideas for Every Season—in 2010 and The Royal Box in 2009, both at Cherry and Martin, as well as No Fixed Points and the characters the Underminer and the Boxer, all felt like they had a shape to me, but not a conventional one. I felt from the way the videos came together in the space that something had happened, some experience had occurred that revealed itself over time. Do you feel like you’ve abandoned narrative entirely, or do you still feel it might have a place in your work?

BB: You’re right in some ways. I’ve chosen to set those sorts of narrative aside for the time being. I think I had some specific goals when it came to engaging the agenda of painting, and to do that I had to take a break from some of my interest in narrative. I’ll go back soon.

AB: This is probably a super-annoying question, but I am curious what artists, writers, filmmakers, politicians, celebrity athletes, et cetera you draw inspiration from. Also, who are your peers with whom you feel an affinity? If this is too annoying you don’t have to answer.

BB: One piece I made not too long ago, Organizing the Physical Evidence (2014), was a combination of my love for Oskar Schlemmer’s Triadisches Ballett (1922), Öyvind Fahlström’s variable paintings, and Mr. Potato Head.