Yuri, you’re putting in The Challenge for the Biennial of Moving Images 2016. A film shot in Qatar – why Qatar?

What stories were you following that took you all the way to the desert in the Arabian peninsula?

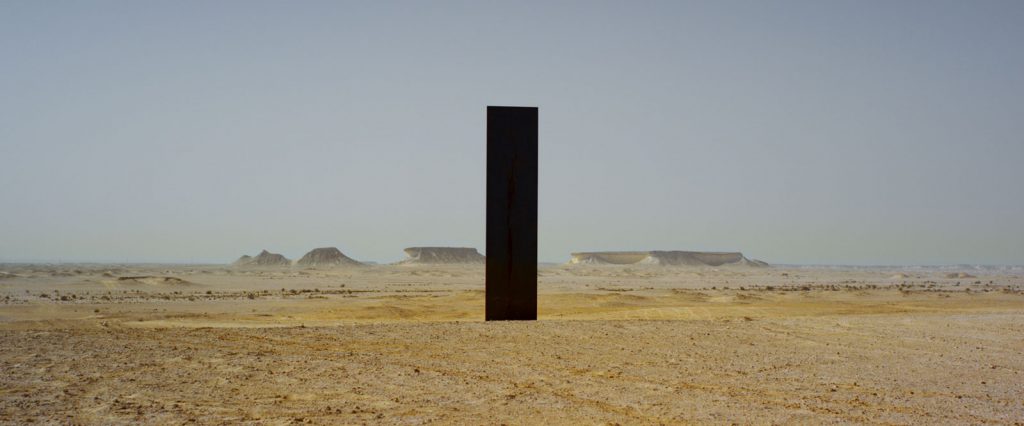

We suddenly found that there’s a country called “Qatar”. Their aggressive approach in the world of real estate – they recently bought the Empire State Building – and in the world of art, finance and politics really intrigued me. The men of power in Qatar are all around us, but we don’t know them.

A.B. The Challenge is a film that revolves around a certain idea of wealth. What impression did you have when you came into contact with people who fly in private aircraft, surround themselves with hunting falcons, and ride gold-plated motorbikes?

Y.A. When The Challenge premiered at the Locarno Film Festival, and the audience asked the falconer, Khaled – the protagonist – what he thought about the film, he replied: “It doesn’t seem like a film, because it’s real life. It’s just normal!” That’s amazing, but this really is normal life in the Qatari desert, and it became normal for me too.

A.B. What was one of the key moments while you were filming? What struck you most?

Y.A. Nasser, the gentleman with a cheetah as a pet, was someone I met on Instagram. I knew he lived in Doha, so I did all I could to find him and in the end I tracked him down. I just had to have him in the film!

This naturally led to some interesting consequences, but I knew right from the outset what I was getting into.

The most surprising situations, however, are those that arise when you least expect it… like the moment of prayer during the trip with the Harley-Davidsons, or the scene of the souped-up car that tries to drive up a sand dune from a standstil. One moment I found incredible was when they cooled down the engine by filling the tanks with water and ice – when you think that water costs far more than gas over there… When I saw them carrying out this operation in front of me in the dead of night, I was really excited and astonished.

A.B. What, on the other hand, do you think you missed? What take would you have liked to do better or even redone from scratch?

Y.A. I wanted to have weapons in the film. I put a lot of work into looking for a gold-plated machine gun – the ones they traditionally use at weddings for a spectacular moment and a great adrenaline rush. But when I found myself looking at those souped-up all-terrain vehicles with flaming exhaust pipes that fired until they’d created holes in the sand… I felt I could do without. Those pipes are more powerful than any spray of bullets! I can say that, metaphorically, there are indeed weapons in the film.

A.B. What makes this film different from the ones you’ve made so far?

Y.A. I don’t think there’s any difference – the music, maybe, composed by Lorenzo Senni and Francesco Fantini, was for the first time played not on a computer and synth, but by an orchestra.

A.B. It doesn’t appear that your aim is to be critical, showing the opulence and wealth of a minority, in a world in which poverty is still a tragedy of biblical proportions… It seems to me you’re not trying to condemn or pass judgement. Is that right? If it is, what’s your intention as a director?

Y.A. I don’t think there’s any point judging: all you need do is look.

This work is one of the few – extremely few – made in the country by a “foreigner”. In actual fact, all the acquisitions and productions in the field of art and cinema are made by Qatar on extraterritorial works.

In my films I never express my point of view out loud – I prefer to remain in silence, and in silence I guide the viewer. It’s important for the spectators themselves to have an experience and to draw their own conclusions from it. This film is certainly the most silent of all, especially in the silence of the closing credits, which is when you have to deal with everything I’ve forced you to see.