For Rua de Mão Única (One Way Street, 2013) you use a Walter Benjamin quote as a route into the work. The destructive character sees nothing permanent. But for this very reason he sees ways everywhere. Where others encounter walls or mountains, he sees a way. But because he sees a way everywhere, he has to clear things from it constantly. Not always by brute force; sometimes by the most refined means. And because he sees ways everywhere, he always stands at a crossroads. At no moment can he know what the next moment will bring. What exists he reduces to rubble—not for the sake of rubble, but for the sake of making his way through it.

It feels as if each of your works ups the ante on the last. And the videos have become more and more incendiary and revolutionary, less playful and more intense. Can you talk about this?

I think that the incendiary, revolutionary force you identify in Rua de Mão Única, and which can be found in all our works, stems from Tiago’s research. Maybe in my videos this engagement is dealt with in a more playful and more controlled way. Paraphrasing Paul Valéry, barbarism is the era of facts, and therefore the era of order must be the empire of fictions. The films that Tiago makes are always more destructive and more troubling. There is an inversion in our processes: it is in the disorder of things (and of my process) that I arrive at a synthesis of sorts that helps me organize the world (and my thoughts). Tiago faces the order of things head-on, and maybe this is why his work has this cathartic force. On the other hand, when we work together, these two facets resonate in the process: it is in a zone of conflict that we carry out our dialogue and vice versa.

In this dialogue-confrontation with Tiago, I tend to test the limits of the disorder of creation; our joint works are less controlled. That is the freedom of working in partnership. This tension comes about, in fact, because we are very authorial in our respective areas. I come from the visual arts, an area that is much less bureaucratic than Tiago’s, cinema. On the other hand, I have a love affair with cinema; that possibility of finding everything within a film has always been inspiring to me, just like that strong characteristic of cinema, of bringing everything (all the arts) together to create a new present, an act of re-actualization.

My experience of Os Residentes (The Residents, 2010), the first project that I made with Tiago, was very intense and also very arduous. Making a film can completely take it out of you. I am still somewhat traumatized. Re-creating a whole world is the slightly insane task to which filmmakers dedicate themselves. In our case, we create everything to then destroy it. The best thing was to have taken part in the process since the beginning of the elaboration of the script, to have had a daily dialogue with Tiago and then with a very young and adventurous team.

GD: I vividly remember watching Automóvel and finding an echo in Jean-Luc Godard’s Weekend (1967) and also Julio Cortázar’s short story “The Southern Thruway.” Automóvel really captures the breakdown in society. Watching Rua de Mão Única for the first time, it was like watching the gang in John Carpenter’s Assault on Precinct 13 (1976). O Século and Rua de Mão Única feel very connected, and I am interested to know whether they were conceptualized together?

Before you answer, let me quote from Roger Ebert’s review of Weekend: “Weekend is about violence, hatred, the end of ideology and the approaching cataclysm that will destroy civilization. It is also about the problem of how to make a movie about this. . . . The traffic jam shows us a civilization that has gotten clogged up in its own artifacts.”1

Also, have world events such as the Arab Spring, the Occupy movement, and the anti-austerity protests had a bearing on your work in recent years? O Século and Rua de Mão Única feel very prescient and political.

TMM: There is always a certain amount of tension and confrontation when Cinthia and I are on set together. We have a competitive side, but it generally works in our favor, because we almost always know where we want to go and the work involves persuading others to walk in the same direction and with the same level of energy, to engage them in the act of creation. For my part, I have a, shall we say, Fullerian tendency: a film is like a battleground. Samuel Fuller used to say, “love, hate, action, violence, death.” A film is a state of exception; art is a state of exception.

So, to begin to answer your question, our films became more incendiary perhaps because we started admitting (formalizing) the violence in and around us. Brazil is a very violent country that is incapable of acknowledging its own violence. And what was research turned into a method. Since then, since the Arab Spring or even before, I was intrigued by Giorgio Agamben’s book on the state of exception, this portrayal of the contemporary world as a state-of-exception-become-rule. We were already obsessed with it, even before it turned into the reality we live in in Brazil. In fact, I have been working on a film for the last four years specifically about this, Os Sonâmbulos (The Somnambulists). So, to me, both O Século and Rua de Mão Única are a Benjaminian branch of this research, like an archaeological dig used as a privileged entry point into the present.

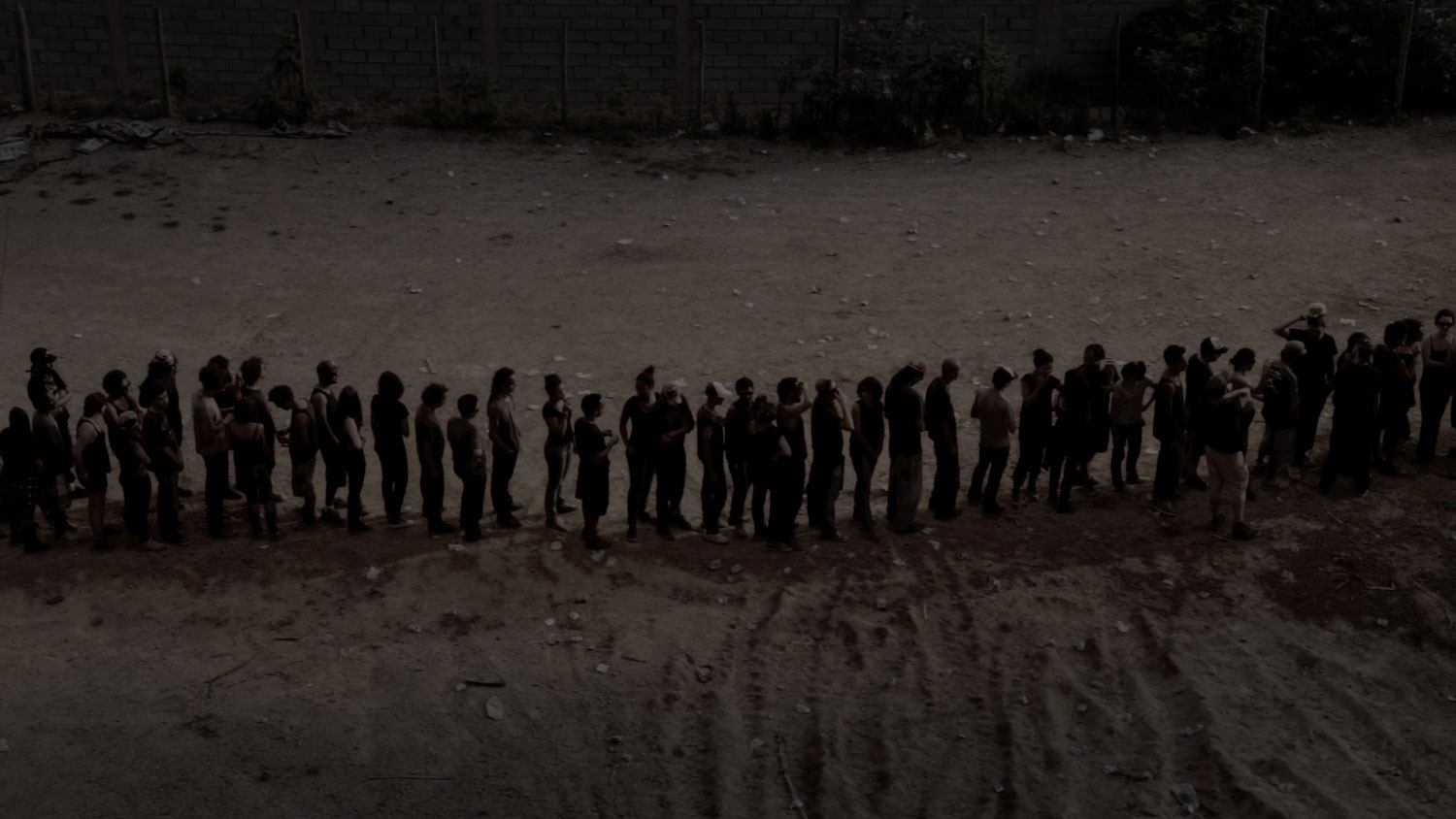

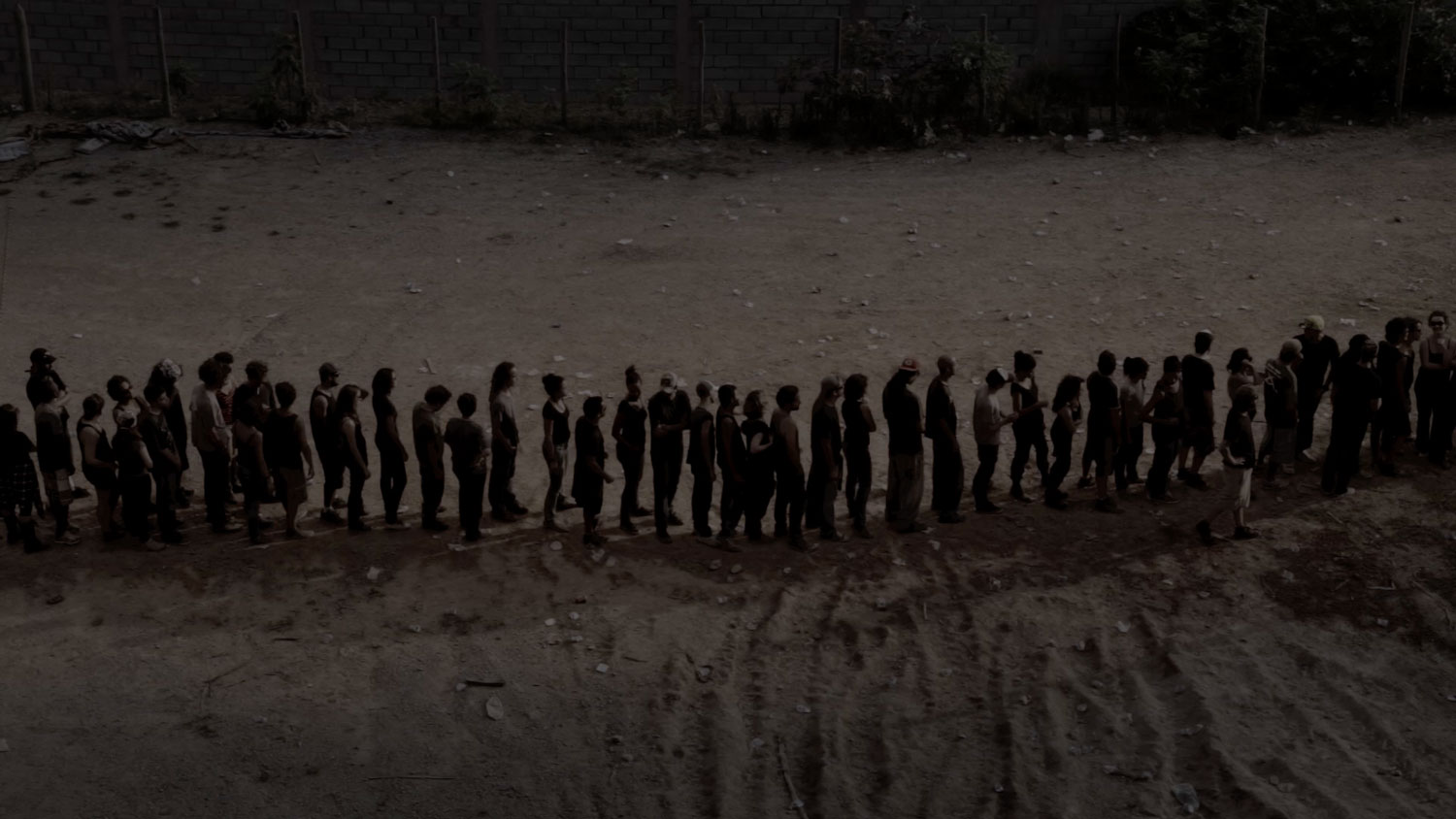

If you think retrospectively, O Século was filmed two years before the protests in Brazil in June 2013, which is the closest we’ve come recently to having an insurrection in the country. O Século is the pre-June (I would even say the proto-June) and Rua de Mão Única is the post-June, when the Black Blocs had already entered the scene (in this case literally, given that we had invited them to take part in Rua de Mão Única). So, above all else, these films reflect the state of things, but this same state also runs through our partnership and through our relationship more generally. So, in a way, we were bursting at the seams.

I think it was when we were making Buraco Negro that we understood that our partnership had to involve some level of confrontation; it had to take on the tension between us, but that was already a residue from a previous experience (because one process always reverberates in another). In fact, the first work we did together was a full-length film, Os Residentes, a film that reflects at length on a certain enchantment that I have with the possibilities of a creative life, in the context of a couple that Cinthia introduced me to at the time, but which was already tinged with a certain critical (Debordian) disenchantment with regard to the role of the artist today. In a way, it was a film about the death of the avant-garde and about the impossibility of a true dilution of art in life now, but which, nonetheless, attempted to a certain degree to reanimate that feeling within the conflictual and hierarchical bounds of a film set. When I look at Buraco Negro today, it is almost like a process of cure and regeneration in relation to the ambiguity and residual tensions of the process of filming Os Residentes.

From that moment on, the art market began very much dictating our rhythm of production, especially Cinthia’s, of course, because I entered the art world on piggyback. If I kept to my natural rhythm, I think I would direct one full-length movie every four years, and that doesn’t satisfy me anymore. I’m a lot lazier than Cinthia. I think I infect her rhythm with some of my laziness, while she has taught me to be more creative and confident.

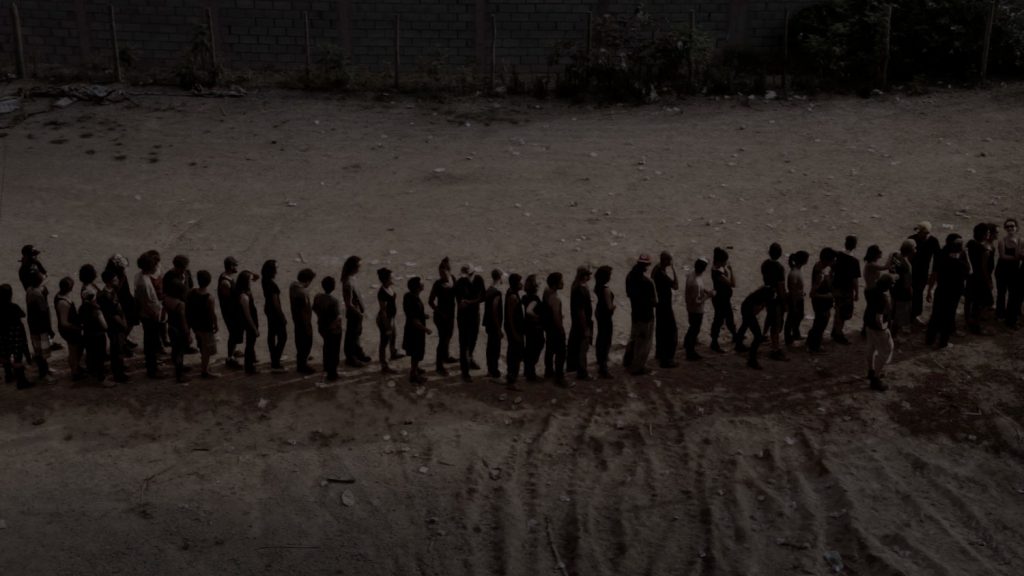

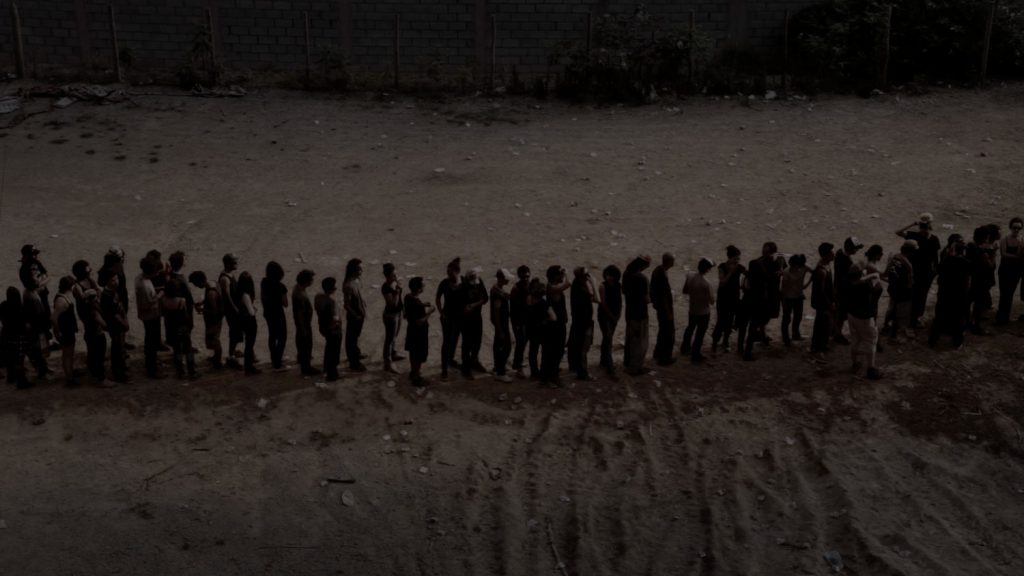

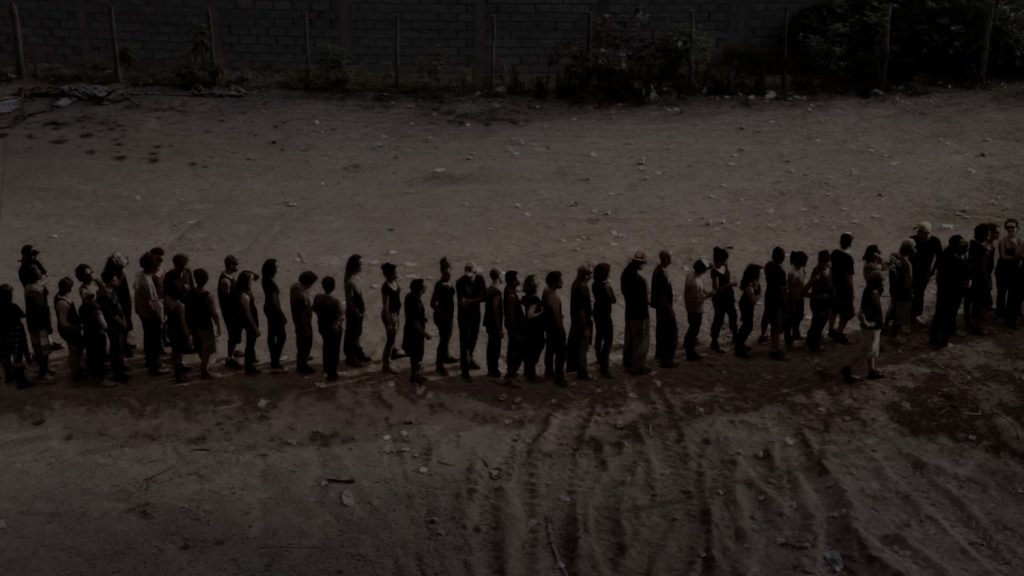

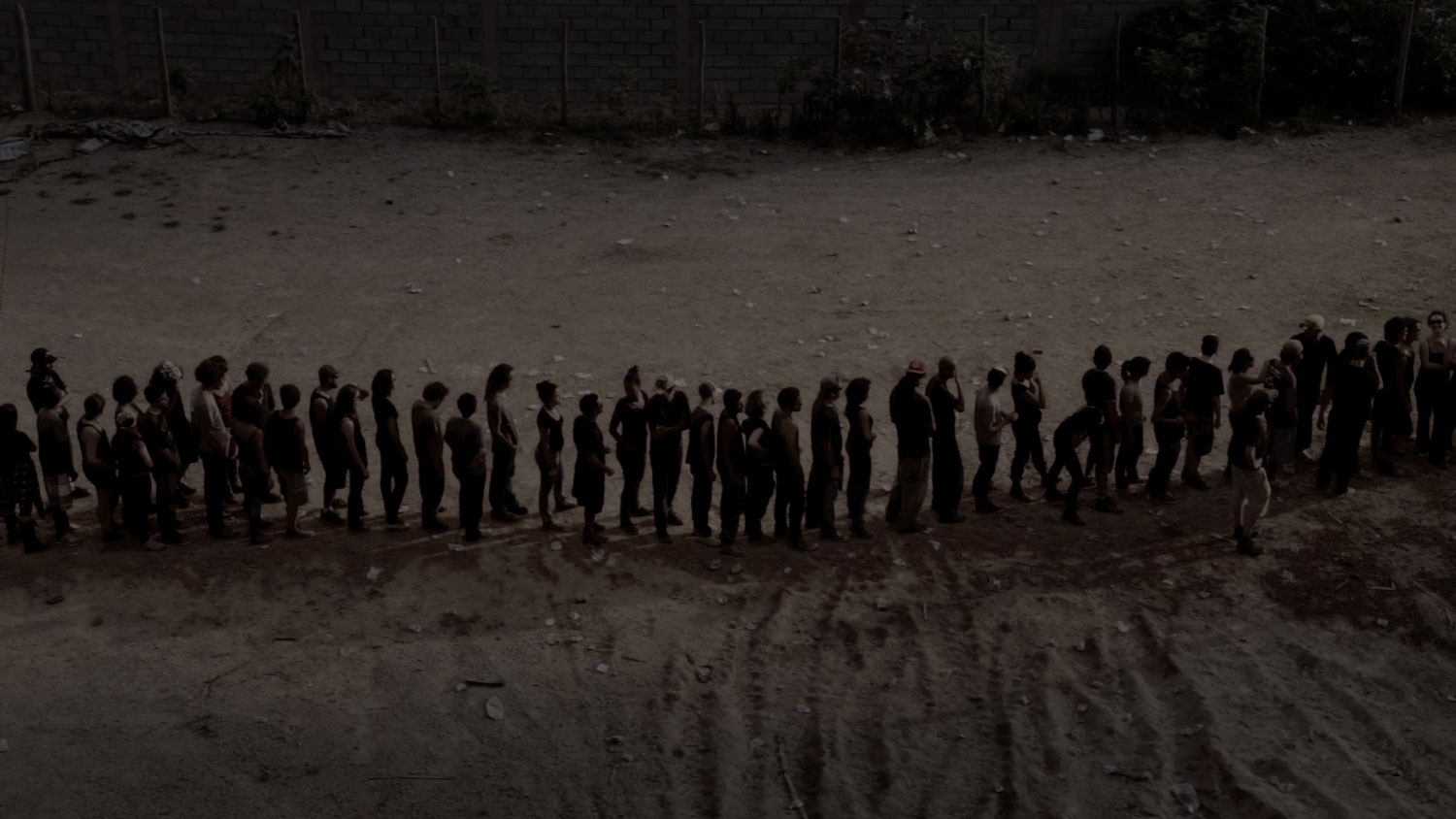

GD: I am always struck by the conviction of the participants in your works. Concerning the new work Community, it seems to me that the conflict is happening on-screen more than offscreen. And it feels like it encapsulates several of your video works from over the years. It makes me think of Sigmund Freud’s adage of “remembering, repeating, and working through.” Of course it is also interesting to showcase Community, a work about order and disorder, in a city that is synonymous with diplomacy: the Geneva Conventions, the United Nations, the Red Cross.

TMM: To me Community is an image of the social contract in Brazil, always ready to be broken, always stable in its instability. We live in a delicate balance, at the edge of the abyss. From an institutional point of view, our republic’s history is a succession of coups d’état and plots intended to bring about change so that everything stays exactly the way it has always been. We live in an oligarchic state of law, not a democratic state of law. There isn’t and there never has been any legal normality in this country because, since the very beginning, since its colonization, Brazil served as a laboratory for mercantile capitalism. The colonial state was always a state of normal exception, and we live simultaneously within and out of the law.

In reality, the only law that has ever reigned in this country is the law of the market. From a civilizational point of view, we are a farce; we can’t even speak of a civilization-barbarism dialectic in our history. We should just admit our barbarism, because, at least in that way, we would free ourselves of our deceit, and also because we have a lot to learn from it, from the savage Amerindian thought, for example. In any case, to me Community is like a portrayal of this society that is always on the cusp of dissolution, of chaos and barbarism, engaged in a constant struggle to rebuild itself.

CM: To add to what Tiago said, Community reinforces the idea of a cycle, the continuous conflict between order and chaos. Nothing is permanent except for change, the illusion of order that humanity tries to project onto everything that surrounds it, onto the instinctive disorder of everything. In Community there is the dissolution of a certain dominant belief that we live in a society that is completely administered, pacified, and controlled by norms (real prisons of space and of the imagination): habits of a system that does not even consider the power of the subjectivity of a social body. On the other hand, the confrontation played out in the video seems to arise from an internal conflict, from bodies colliding; ultimately it is the very system that drives us to break its rules and that makes us violent. As Jean Baudrillard said: by dealing all the cards to itself, the system forces the Other to change the rules of the game, and the new rules are fierce because the game is fierce.

Note

- Roger Ebert in the Chicago Sun-Times, April 11, 1969, http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/weekend-1968.